When trying to figure out and predict a buck’s pattern, the author believes weather, type of day, stress, and other variables have a major influence.

Bucks in most areas won’t move in regular, clockwise patterns. Their movement in most areas is roughly circular, simply because they come into an area on X trails and leave that area on Y trails, even if they’re just going from bedding to feeding areas and vice versa. This limits their exposure, removes the predictability. They all have more than one bedding and feeding area, too, which lowers predictability even further.

So, I doubt whether you could say “I saw a buck there two nights ago. He should be passing through again tonight.” There is a lot of wandering in deer movements. Under the circumstances of trying to figure out and try to predict a buck’s pattern, I believe weather, type of day, stress and other variable conditions have a major influence. A buck may want to from point A to point B, but coon hunters push him off his path and he goes to point C to feed and bed down. A day or two later, he may or may not reach point B. He doesn’t need to. He doesn’t need to e home for dinner. He doesn’t have to meet anyone at a certain street corner at a specific time. He doesn’t have to cross a field in a certain number of minutes. He just wants to exist in the best and safest manner. That’s why the deer takes what is given to it, and, I believe, reacts more than acts. (You know yourself how a shot situation works out the best when you don’t force it, but wait out a deer and let its actions dictate what you do or don’t do.) Hiding under a bush or in a thicket and letting a hunter walk right past within 10 yards is a form of reaction…inactive reaction, a non-response response.

A big buck is almost impossible to predict. He knows when there’s hunting pressure or other people pressure, and he’ll just change his pattern enough to get by. He’s as adaptable as they come.

A yearling buck is pretty predictable. He doesn’t have the experience a big buck does, and his system isn’t geared as slow. He doesn’t have the control of himself that a big buck does. Hunting a yearling buck is about like hunting any yearling.

Accept your hunting tool’s limitations and learn to hunt well enough to place yourself in the right position for a good shot at an unalarmed animal.

The only times you can figure to pattern good bucks are in late summer before the season opens while they are still in their summer movement patterns and during the late season when snow ground cover, absent foliage and less available food make them more visible, travel farther and give you a record of their movements.

A deer’s range isn’t that large. For it to survive as well as it does, and go unseen as much as it does, it has to have excellent survival instincts and training. If it was easy to pattern, the whitetail would be only a memory instead of the number one big game animal.

Food availability seems to be a key to how well defined or poorly defined the patterns are, except during the rut. In my areas, there is so much food the patterns are loose. In an area with fewer food sources and/or terrain changes that force them to be more habitual, I would expect it to be easier to pinpoint individual animals and good bucks.

Any time any type of restriction comes into play, the deer loses an option or two. You pick up a point or two, then, in your odds.

Since deer foods vary from area to area within a state, and from region to region, it pays to study food consumption reports. State DNRs often have such reports. State agriculture departments often have percentage-of-the-crop-harvested (corn and soybeans, mostly) reports. There are popular literature and all sorts of biological reports to study. Make use of that information.

The Right Attitude

While you’re doing this, be sure you develop the right attitude. You get that right attitude from proper scouting, proper equipment preparation, proper practice, proper hunting technique. You know what you can hit at 20 yards or thereabouts. Those positive items will click into place as you prepare all of them. Just be sure you do not rely on your shooting ability as a crutch. Too many people do.

You have to do all things right to get the animal into range, or let it get into range.

That comes with having the confidence in yourself and the stand or stands you selected. Without that confidence in the stand and yourself, you won’t be able to stand for five or six hours; you’ll be thinking, “Maybe I should be over there … or over there … or there.

Have confidence in your ability to select the best possible stand for that given area, and this will give you more confidence because you’ll know that you’re going to have more shots passing you at 20 yards than if you moved over another 50 yards. Fifty yards in the wrong direction can do more than reduce the number of good shots. It can keep you from seeing deer, which would do absolutely no good for your confIdence or for your open tag.

You have reasoning and thought ability working for you, if you use it. Do the early scouting. Figure things out. There’s a lot of difference between knowing, wondering and hoping. If you take the time to do the prep work right, you’ll know.

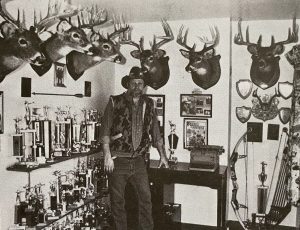

Fratzke is adept in the woods and on the field and target ranges. To be consistently successful, a bowhunter needs to be able to find the deer and then hit them solidly when he finds them.

Bob Fratzke, the Author

Bob Fratzke, a Minnesota native, knows whitetails. His trophy room walls attest to that. He does NOT hunt for individual, specific trophy bucks, because too often that leads to the hunter patterning himself and spooking the deer. He scouts and hunts with open-mindedness and mental flexibility, being sure that he is as adaptable as the whitetail deer. When you do your scouting homework, the hunting takes care of itself as long as you learn to read the woods, seeing what you’re looking at instead of what you hope to see, and then putting those signals to work for your hunting success. Consistently successful whitetail hunting means seeing details — and paying attention to them.

TAKING TROPHY WHITETAILS is 140 pages, 5.5″ x 8.5″, paperback. It was published by Glenn Helgeland’s TARGET COMMUNICATIONS OUTDOOR BOOKS as part of his Outdoor Sports Series.

It is available on the publisher’s website — www.targetcommbooks.com.